Countless

Chuck Christian (second row, sitting above #53) in the 1980 team photo [Bentley Image Bank]

Content warning: descriptions of sexual abuse.

Chuck Christian is dying of prostate cancer. He's 61 years old.

Christian came forward as one of Dr. Robert Anderson's many victims of sexual abuse over a year ago. By that time, he'd already outlived the terminal prognosis he received four years earlier. His story is devastating.

It was as much odd as it was alarming, then, when Christian started to find blood in his bodily fluids in the early 2000s. He begrudgingly made an appointment to get checked out. After a few tests, the doctor informed Christian that he needed a digital exam to make sure his prostate was functioning properly. Christian assumed that would mean some type of technological scan followed by images on a computer screen. Then the doctor turned to pull on a pair of gloves and lubricate his finger.

"Just hearing that glove snap, it was like, 'Oh, God, no,'" Christian said. "I just kind of freaked out. I said never again. So I left, and we never had the test done."

Christian's wife finally insisted he see a urologist and go through with a prostate exam when he began waking up to go to the bathroom "a dozen times a night" in 2016. He'd never told her why he so resisted seeking medical treatment.

In fact, at least in part because Anderson remained a respected figure within Michigan's athletic department, Christian didn't consider himself a victim of sexual abuse until a former teammate informed him of another victim's letter to Warde Manuel—and a burgeoning number of former athletes saying they'd been violated by Anderson, too.

Anderson worked at the University of Michigan from 1966 until 2003. When he died in 2008, his peers spoke fondly of him.

Former Michigan football coach Lloyd Carr, who once worked with Anderson, said people used to joke that Anderson was the poorest doctor in Ann Arbor because he worked for the Athletic Department at a lower pay rate than what the average doctor would make.

“If any of us didn’t feel well or had the flu or our kids were sick, we had the comfort of knowing that he was going to drop what he was doing,” Carr said. “He was a tremendous asset in this community.”

For four decades, Christian didn't believe he was a victim. This is the abuse he experienced.

He waited in a lobby for several minutes, along with another freshman from the football program, before going to Anderson's office alone. The short, stout doctor ran through some routine tests. Then Christian says Anderson told him to remove his shorts and bend over the exam table for a purported prostate exam.

Christian says he howled while Anderson put his fingers inside of him.

"He was a fat doctor with fat fingers. That hurt like crazy," he said. "I was screaming in pain, but I knew not to scream at him because I knew I had to do that to play. It wasn't going to do me any good to scream at him."

Christian remembers leaving the exam room and spotting the classmate who had been with him in the lobby. Christian's face prompted the other young man to ask if Anderson had done it to him, too.

"Oh, yes, what was that?" Christian said. "I feel violated."

"Me, too, man," the teammate said. "Me, too."

There's no medical reason to conduct a prostate exam on a healthy 18-year-old. Christian stayed in the football program for four years, as champions do, and saw Anderson for a physical prior to every season. He didn't mention continued abuse to an authority figure. It was just how things were done at Michigan; after all, Anderson had been a team doctor since 1967, and Christian feared he'd fail his physical and lose his scholarship if he didn't allow Anderson to violate him.

----------------------

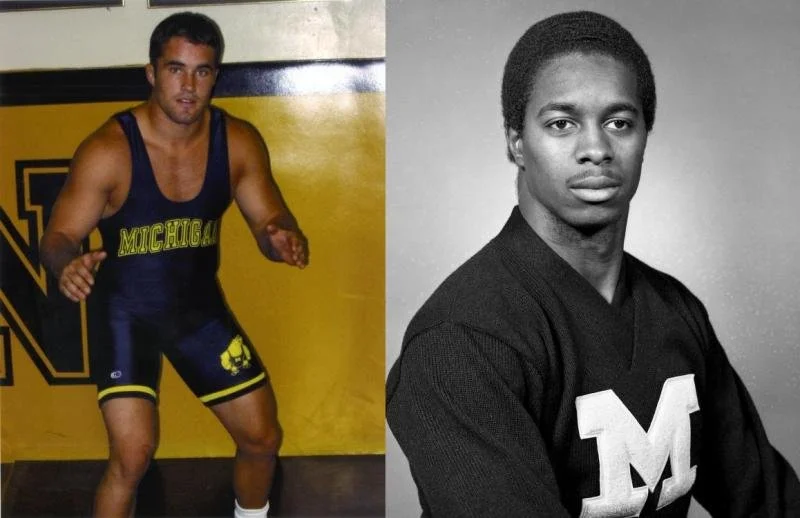

Wrestler Andy Hrovat and football player Dwight Hicks both were abused by Anderson [Bentley]

By the time Christian first saw Anderson, the doctor had a history of abuse, some of which had been reported to authorities at the university. This has been confirmed in reporting over the past two years and the 240-page report released yesterday by the law firm WilmerHale, which the school hired as an independent investigator.

Even if word had somehow not spread around campus about Anderson by the time Christian arrived in Ann Arbor in 1977, a wrestler named Tad DeLuca had already detailed extensive abuse when he was supposed to be receiving treatment for ailments—a dislocated elbow, for instance—that certainly didn't require rectal and genital examinations. According to WilmerHale's report, authorities at U-M continued to ignore repeated warnings about Anderson for decades:

First, in July 1975, Tad DeLuca, a member of the wrestling team, sent a letter to head wrestling coach Bill Johannesen and assistant wrestling coach Cal Jenkins that, among other things, included a complaint about Dr. Anderson. Neither Mr. Johannesen nor Mr. Jenkins inquired about Dr. Anderson’s conduct or referred the matter for investigation by others.

Second, in or around 1979 to 1981, senior University administrator Thomas Easthope received complaints regarding Dr. Anderson’s misconduct on at least three separate occasions. Mr. Easthope, who had supervisory authority over UHS, was told directly and explicitly about Dr. Anderson’s misconduct and failed to take proper action to address it.

Third, the University failed to investigate persistent and widespread rumors about Dr. Anderson. We found that at least some personnel in UHS and the Athletic Department heard or were aware of jokes, banter, and innuendo about Dr. Anderson’s conduct with patients, but they did not recognize such comments as cause for concern.

Fourth, the University did not conduct due diligence with respect to a 1995 lawsuit alleging that Dr. Anderson assaulted a patient during a pre-employment physical. Dr. Anderson himself disclosed the lawsuit on an application for Michigan Medicine credentials in September 1996.

The details of the report are sickening. The section titled "Dr. Anderson's Misconduct" is nine pages largely comprised of bullet-point summaries of accounts from his victims, whom he seemingly chose because of one vulnerability or another—students up for the draft during the Vietnam War, the LGBTQ community, patients who couldn't afford medication, athletes scared to lose their scholarships, and so on.

Their stories are harrowing. So, too, is the section's first paragraph.

Dr. Anderson committed sexual misconduct on countless occasions during his nearly four decades as a University employee. He engaged in practices that were improper in a clinical or educational setting—and would have been improper in any other setting. This finding is based on information received from almost 600 of Dr. Anderson’s former patients and interviews of more than 300 of those patients, approximately ninety percent of whom were male. We recognize that this group of patients represents only a fraction of the total patients treated by Dr. Anderson in University settings between the late 1960s and early 2000s. In all likelihood, Dr. Anderson abused many patients in addition to those who provided information to us.

"Countless occasions." The hundreds of victims who spoke to them representing "only a fraction" of his patient population. Four decades of abuse.

The devastation done to Chuck Christian alone is horrific. It's difficult, if not impossible, to fathom the physical pain, mental anguish, and, yes, years taken from lives caused by Anderson, and how much could've been stopped before it ever occurred.

----------------------

Take it down. [Bryan Fuller/MGoBlog]

Bo Schembechler was in a position to do something about Robert Anderson. Schembechler, of course, was Michigan's revered head football coach from 1968 to 1989, served as the school's athletic director from 1988 to 1990, and until his death in 2006 maintained an office in the building that bears his name.

The idea that the most powerful and visible figure in the athletic department for decades wouldn't have heard about Anderson's abuse, even if just second- or third-hand, strained credulity even before former players said he knew. Schembechler's name appears multiple times in the WilmerHale report. He knew.

A member of the football team told us that Dr. Anderson gave him a rectal examination and fondled his testicles during a PPE in 1976. The student athlete told us he informed Coach Bo Schembechler that he did not want to receive any future physicals from Dr. Anderson and that “things were going down there that weren’t right.” According to the student athlete, Mr. Schembechler explained that annual PPEs were required to play football at the University. The patient continued to see Dr. Anderson and made no further reports about Dr. Anderson’s misconduct. Mr. Schembechler is deceased. The same student athlete told us that his position coach used the threat of an examination with Dr. Anderson as a motivational tool. We interviewed the coach, who denied the allegation.

A member of the football team in the late 1970s told DPSS that he received a genital examination from Dr. Anderson, who fondled his testicles, and a rectal examination, during which the student athlete pushed Dr. Anderson’s hand away. The student athlete told DPSS that he asked Mr. Schembechler “soon” after the exam, “What’s up with the finger in the butt treatment by Dr. Anderson?” According to the student athlete, Mr. Schembechler told him to “toughen up.” The student athlete told DPSS that “you do not mess with Bo, and the matter was dropped.” The student athlete, who is represented by counsel, declined our interview request.

Another student athlete told us Dr. Anderson conducted genital and rectal examinations during a PPE in the fall of 1982. The student athlete told us that during the examination Dr. Anderson “play[ed]” with the patient’s penis and made comments about its size. Following the examination, the student athlete told us he informed Mr. Schembechler that Dr. Anderson had “mess[ed]” with his penis and that he did not “agree” with the type of physical examination that Dr. Anderson performed. Mr. Schembechler reportedly told the student athlete that he would look into it, but the student athlete never heard anything further about it. The student athlete continued to see Dr. Anderson but did not raise the matter again, fearing that doing so could jeopardize his scholarship.

A student athlete alleges that Mr. Schembechler sent him to Dr. Anderson for migraines in the early 1980s. On at least three occasions, the student athlete alleges, Dr. Anderson gave the patient a digital rectal examination. The student athlete allegedly told Mr. Schembechler, who instructed him to report the matter to Athletic Director Don Canham. The patient alleges that he did so twice, in 1982 and 1983, but Mr. Canham took no action. The student athlete’s attorney declined our request to interview his client.

The only defense of Schembechler is a footnote that, given the multiple accounts contradicting it and common sense, probably could've gone unprinted: "Multiple University personnel who worked with Mr. Schembechler told us that had he been aware of Dr. Anderson’s misconduct with patients, he would not have tolerated it."

Bo Schembechler isn't the embodiment of evil. The world isn't that simple. He's no hero, either. He represented himself not just as a football coach but a figure of moral authority and a leader among leaders. By his own standard of leadership, let alone moral authority, he failed.

Schembechler said as much in "Bo's Lasting Lessons," his book on "teaching the timeless fundamentals of leadership" that was directed more towards businessmen than Michigan fans. This is the first paragraph of Chapter Six, which is titled "Do the Right Thing—Always."

Continuing to lionize Schembechler is an affront to Anderson's victims, sexual assault victims everywhere, and the principles of the University of Michigan. The same applies to his longtime athletic director, Don Canham, who was aware of the DeLuca letter and at least one other accusation against Anderson.

There's nothing that can bring justice to this tragedy. Anderson is long dead. So are Schembechler and Canham. The four decades of abuse and inaction cannot be undone, nor their far-reaching consequences. The least the school can do, however, is take down the statue, remove Schembechler's name from the football building, and take Canham's off the natatorium. They will still be remembered. They should not be revered.

Originally published on MGoBlog.