The Creator

In today's basketball world, the corner three is superior in value to any shot that doesn't come at the rim. It's also the toughest shot in the game to create for yourself; to do so requires a silky touch, a tapdancer's precision, and the guts and/or stupidity to launch a shot that would earn most players a quick trip to the bench.

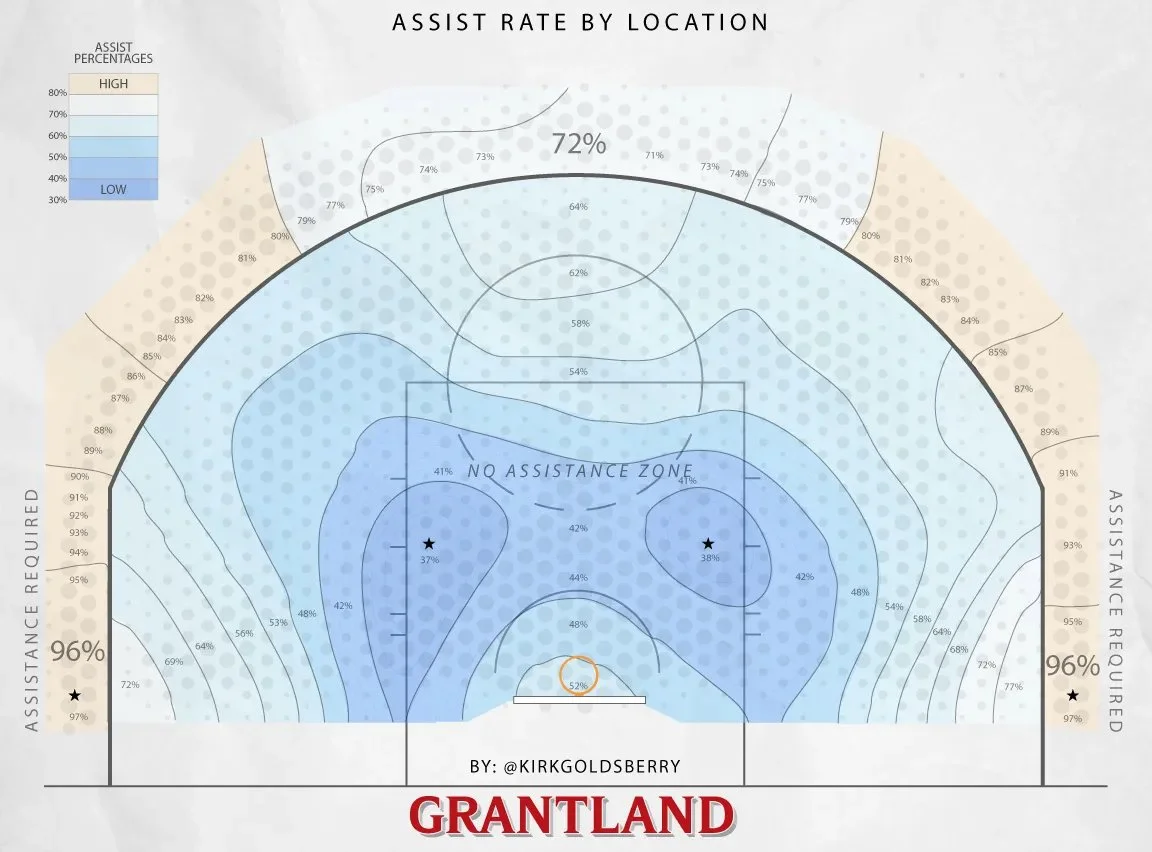

Grantland's Kirk Goldsberry covered this topic in exacting detail yesterday, posting this fascinating chart that shows the assist rate for shots made from each spot on the floor—three-pointers usually require assistance, and the rate increases as the shooter gets closer to the baseline [click to embiggen]:

Goldsberry's post focused on the players who could create those high-percentage shots for their teammates, because even in the NBA, finding players who do it themselves is a difficult proposition:

Meanwhile, unassisted corners 3s are the white buffalos of perimeter shooting. They don’t come around too often. As it turns out, dribbling into the corner and firing up a 3 is very difficult, and perhaps unwise, as well. It takes a special kind of player to even attempt this task, as Rudy Gay demonstrates for us here: [GIF of Rudy Gay dribbling into the corner and badly airballing a fallaway attempt]

Which brings me to Nik Stauskas. I've written before about his pregame shootaround routine, but it's worth mentioning again. In addition to practicing the usual spot-up threes from various points around the arc, Stauskas always spent time in the corner working his crossover stepback, a move designed to clear out just enough space to launch from a spot that opponents long ago learned to keep him from at all costs.

Without ever having to look, Stauskas's feet nestled precisely between the three-point line and the sideline, the product of countless practice hours transforming process into instinct. By the end of his Michigan career, he made these audacious warmup attempts at about the same outrageous clip that he hit his normal shots. Michigan's shootarounds were considered must-watch because of the team's—and especially Glenn Robinson's—impromptu dunk exhibitions; for me, however, the Stauskas Stepback was always the highlight.

It wasn't limited to warmups, of course. There's no point in creating that level of muscle memory without utilizing it when it counted. So, far more frequently than any fanbase deserves, we were treated to the sight of this 6'6" Canadian kid make a mockery of the game's toughest shot—and, delightfully, mark this feat with a turn towards the opponent bench as the ball fell through the hoop.

Of all the facets of Stauskas's game—the remarkable vision running the high screen, the "Game ... Blouses" dunks, the way he fed off and genuinely enjoyed the hatred from opposing fans (and sometimes players)—this is the one I'll miss the most. I'm just not sure I'll ever cover another player who could so routinely find himself in the game's least threatening situation, a ballhandler trapped in the corner, and conjure a dagger.

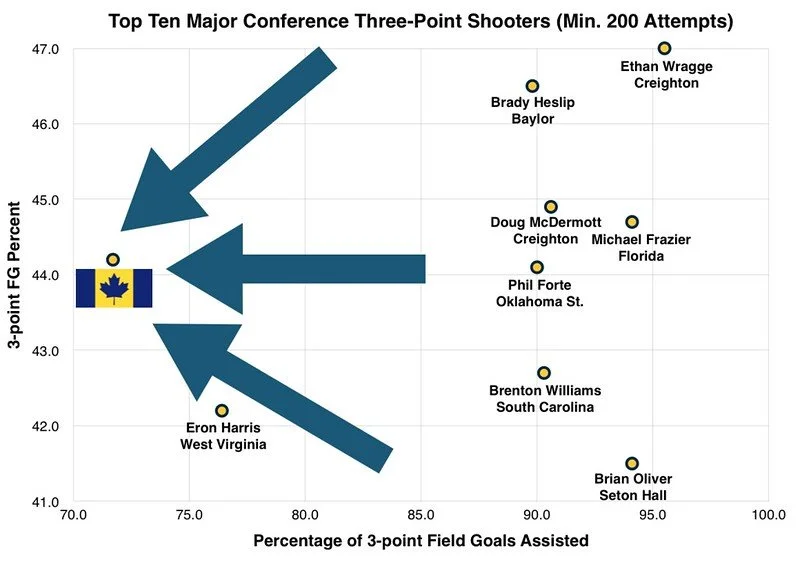

Out of curiosity, I put together a chart of this season's top ten three-point shooters from high major conferences (min. 200 attempts) and combined it with data from hoop-math on the percentage of each player's three-point makes that were assisted. The results were rather astounding [click to embiggen]:

Eight of the top ten benefited from assist rates between Brady Heslip's 89.2% and Ethan Wragge's 95.5%. Eron Harris is a distinct outlier, shooting 42.4% with just 76.4% of his makes assisted.

Then there's Stauskas, who made 44.2% of his triples despite being assisted on just 71.7% of them. Even after watching him play for two years, my jaw dropped while compiling these numbers. John Beilein summed it up perfectly after watching Stauskas drop 21 second-half points on Michigan State in Crisler this season, most of those points coming off an astonishing array of pull-up jumpers:

“He’s looking for a perfect play all the time, and shooters gotta shoot it. I mean, he’s a tremendous shooter. Whether he’s turning down ones off the dribble lately because he’s maybe looking for something else, we want him to shoot the ball. ... We just encourage him to be more aggressive. Aggressive usually means drive the ball. But shooters shoot when they’re open. Sometimes what’s a bad shot for others is a really good shot for him.”

That State game is a great example of Stauskas's often unstoppable combination of size, skill, and body control. Watch the highlight tapes and you'll see him scoring at will off the dribble, stopping on a dime and pulling up whenever he gave himself enough air to breathe. For just about any other player, the shots involve fading away or being off-balance in one way or another. But look at these three photos from our own Bryan Fuller—all of these shots were launched off the bounce:

Looking at the stills, you'd think these were three spot-up attempts that Stauskas managed to barely get off over quickly closing defenders. He elevates in ideal shooting form, keeping his body aligned perpendicular to the court, his eyes on the rim, and finishing with that same sweet stroke each time. Words fail to describe how remarkable it is to make a play like this become routine:

That's Nik Stauskas. Tell him there's a shot he shouldn't take, and he'll work and work and work until it becomes a shot opponents not only have to respect, but gameplan to defend. Cut off his other options and he'll pull a Houdini act, then tell you all about it on his way back down the court. Pin him in the corner and, well, screw it, he'll hit the shot from behind the damn backboard if he must.

He did this while playing within the confines of Beilein's offense—Stauskas took a smaller percentage of the team's shots when he was on the floor than Robinson, even though the go-to guy was obvious to all. He played his part, and when all else broke down, he created shots that mere mortals simply hope will come to them. And he made them so often it almost (almost) stopped being amazing.

But every time Stauskas came out for warmups, I watched agape. Then he'd pull it off in games, turning bad shots into good until we no longer went "no, no, no..." before the "YES!"